Current laws around casual work have caused widespread confusion among businesses, but that is set to change after parliament passed IR reforms this year. We outline what the key changes mean for business.

The Attorney General has said the previous laws around casual work have exposed businesses to billions of dollars in back pay.

The Federal Government’s changes to the Fair Work (FW) Act create a clearer framework around casual employment.

The legislation seeks to remedy uncertainty and unfairness that arose from recent court cases around casual work.

CCIWA Workplace Relations Director Ryan Martin Martin outlined the key changes to casual work definitions and their anticipated impacts during CCIWA's recent HR Quarterly event.

The Fair Work (FW) Act’s omission of a statutory definition around casual work led to confusion and uncertainty for employers and employees, as highlighted in the Rossato and Skene cases.

These Federal Court decisions both signalled that in absence of a statutory definition, the courts would be very open to considering a range of factors in determining whether an employee is casual or not.

This created a great deal of uncertainty and risk for employers, leaving businesses exposed to billions of dollars in entitlements.

Drawing on common law principles, the definition of a casual worker under the amended FW Act is:

Someone who is offered employment on the basis that the employer makes no firm advance commitment of continuing and indefinite work according to an agreed pattern of work.

If this test is met at the time an employee commences work, they will remain a casual unless they convert to full or part-time employment.

If they commence a job with a firm advance commitment to ongoing work, they will not be classified as a casual worker under the legislation.

As Martin explains, the meaning of ‘firm advanced commitment’ in the Act takes into account several factors, including whether:

- the employer can elect to offer work;

- the employee can elect to accept or reject that work;

- the employee will work only on demand or as required;

- the employment is described as casual;

- the employee will be entitled to a casual loading or a specific rate of pay for casual employees under the terms of the offer of employment.

To allow employers time to transition to this new definition, the law contains transitional arrangements, providing employers of current casuals with a grace period before the definition will take effect.

The new definition of casual will apply retrospectively and prospectively. This is aimed at preventing double payment scenarios such as in the Rossato and Skene cases.

Since 2001, some awards have included the ability for an employee to convert from a casual to a full or part-time worker, but the proposed legislation extends that to all employees.

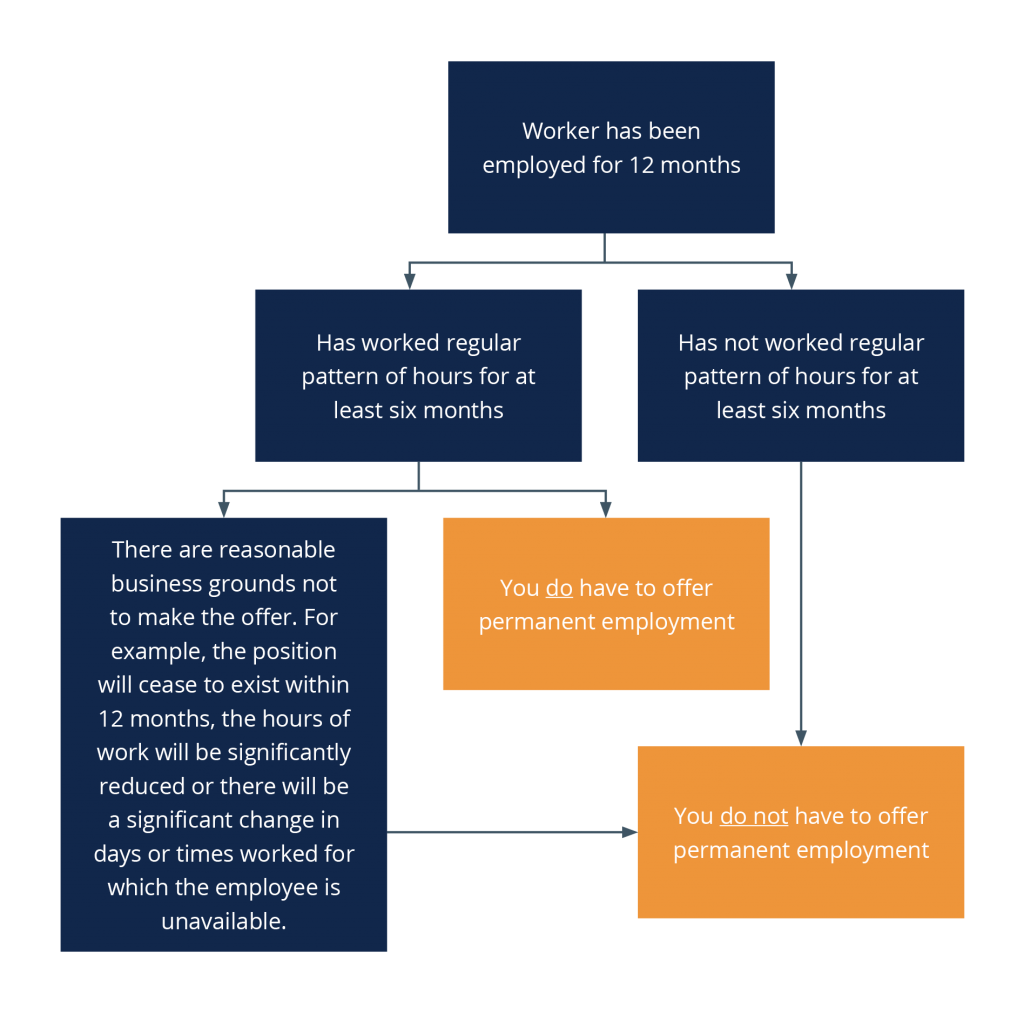

“Employers of casual workers will be required to offer part time or full-time roles to casuals after 12 months, if they have worked a regular pattern of hours for at least the previous six months, unless the employer has reasonable grounds not to,” Martin explains.

Martin says while this provision will provide greater clarity around when a worker is and is not defined as a casual, it was important to be aware of the legal implications of enshrining this into the FW Act.

The law proposes to include this into part two of the Fair Work Act, which means it will be included in the National Employment Standards.

He adds that as a result of its inclusion in the FW Act, the provision would be a workplace right, which means it could potentially give rise to general protections claims.

“You'll need to have good evidence of any genuine business reasons what you intend to do things like reducing casuals employees shifts, or other steps that might be considered adverse action around the time that this right becomes available to a casual employee," he says.

He stresses the importance of obtaining advice when undergoing this process.

The casual conversion provision will include a six-month grace period of six months, for employers to assess their employees’ entitlements and potentially initiate the conversion process.

Small businesses with less than 15 employees will be exempt from these provisions, although will need to comply with a relevant award provision.

The offset provision will also help to prevent the occurrence of double payments, such as in the Rossato case.

“This seeks to resolve the potential for these double payment claims where an employee is engaged as a casual and paid an identifiable amount in lieu of one or more of the relevant entitlements and the employee is ultimately determined not to be a casual and seeks to be back paid,” Martin says.

“So essentially, what that means is, if you've already been paid for something, the court will consider that and offset that amount against anything that you're claiming you're entitled to because you are actually a permanent employee.”

The FW Act amendments were reviewed by a Senate committee, which handed down its report in mid-March.

The amendments included changes to enterprise agreements, modern awards and Greenfields agreements, which did not pass.

The Bill took effect on March 27, after debate in both houses of Parliament.

WorkPac v Rossato (2020)

In May 2020, the Federal Court ruled a “casual” worker could claim leave entitlements, forcing businesses to reexamine their workforce arrangements.

The ruling reinforced that casual employees with “predictable periods of working time” are likely to be considered permanent.

This has implications for casual loading—which is the extra money businesses pay casuals to compensate for the leave entitlements that permanent staff members receive.

For guidance, contact CCIWA’s Employment Relations Advice Centre on 9365 7660 or [email protected].